Blind Boxes

Monte Carlo Methods and Bob’s Burgers

In this article we are going to use ‘Monte Carlo’ methods to investigate certain probabilities related to collectibles known as ‘blind boxes’. These blind boxes are like real life versions of ‘loot boxes’ which we you might be familiar with from video games.

Motivation: I recently bought two blind boxes containing collectible pin badges, based on the animated series ‘Bob’s Burgers’.

What is a “blind box”?

A blind box is a sealed box and contains a sealed foil sleeve inside, when you open the sleeve you will find a badge. There is no way of knowing without opening it what badge you have inside, and so when you buy it you are taking a chance that you will get a badge you want or don’t already have. On the back of the box you can see all the available badges, and the probabilities of getting each of these badges.

This raises some interesting mathematical questions, which we will address in this post.

Part 1: When to expect your first disappointment

This was my first time buying a Bob’s Burger blind box, and so for the first box it was bound to be a badge I didn’t have. There are 16 different badges in total, and so for the second box I bought it was also very unlikely that box would contain the same as the first. However, the more boxes I buy, the more likely I am to get a duplicate - a badge I already have. For example suppose I already own 15 of the 16 badges, then when I buy a new box we might expect that I am more likely to get a duplicate than to get the missing badge and complete my collection.

The first question we will look at is when should we expect our first duplicate badge.

Part 2: I can’t stop buying badges

Even once we get our first duplicate badge, we still might feel we want to keep buying more badges because we feel like we are more likely to get a new badge than a duplicate. We investigate the question at what point am I more likely to get a duplicate?

Part 3: Gotta catch them all

I want the complete collection. If I keep buying blind boxes, how many would I have to buy to get the complete collection?

So what’s a Monte Carlo Method?

To answer these questions we will use Monte Carlo Methods. These are methods which involve random simulations. They are extremely powerful and can be very useful when trying to solve a problem analytically is too difficult or not possible.

All of the essential code is included within the post. For brevity I do not include the plotting code nor the imports, which are standard.

Part 1: When to expect your first disappointment

To begin investigating the problem of buying Bob’s Burgers Badges (that’s a mouthful), we need to know the probability of getting each of the given badges. Helpfully on the back of the box we can see the probabilities.

Most of the 16 badges have a probability of 1/20, but 4 of them are slightly more common with 2/20.

Python Approach We will create a numpy array with each of the badges in it, the badges that have probability 1/20 will appear once and those with probability 2/20 will appear twice.

probs = np.array([

'Bob Belcher',

'Bob Belcher',

'Linda Belcher',

'Tina Belcher',

'Tina Belcher',

'Bad Tina',

'Gene Belcher',

'Gene Belcher',

'Gene Burger',

'Louise Belcher',

'Louise Belcher',

'Kuchi Kopi',

'Jimmy Pesto',

'Jimmy Pesto Jr',

'Ollie',

'Andy',

'Hugo',

'Calvin',

'Gayle',

'Teddy']

)

So we have each of the pins in this array, and if we randomly (uniformly) select an item from this array, we will be selecting it with the same probability as if we had bought the blind box. We can use this to run a simulation.

# Example simulating buying a Blind Box

np.random.choice(probs)

'Jimmy Pesto'

Our first question is about understanding when I will see my first duplicate badge. We create a simulation below which simulates buying blind boxes until you get a duplicate badge. (In this article I am writing my code to be clear and understandable rather than fast.)

def simulation1(n_trials=100, print_output=False):

purchase_saw_first_duplicate = [] #Which purchase was my first duplicate.

for i in range(n_trials):

collection = [] #Our collection starts empty each time

while len(collection) == len(set(collection)): #We will keep adding things to our collection until we get a repeat

collection.append(np.random.choice(probs))

#Once we have a repeat, we append this length

purchase_saw_first_duplicate.append(len(collection))

if print_output == True:

print(collection)

if print_output==True:

print(purchase_saw_first_duplicate)

return purchase_saw_first_duplicate

For an individual simulation we might get:

[‘Gene Belcher’, ‘Louise Belcher’, ‘Teddy’, ‘Gayle’, ‘Tina Belcher’, ‘Gene Belcher’] as our collection, then our first duplicate was on the 6th purchase. We would then append the number 6 to the list purchase_saw_first_duplicate.

simulation1(n_trials=1, print_output=True)

['Andy', 'Bob Belcher', 'Tina Belcher', 'Tina Belcher']

[4]

[4]

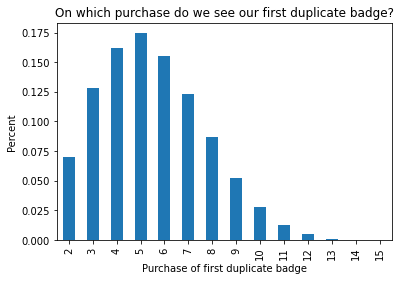

For our Monte Carlo simulation to work properly, we need to run a large number of trials… We run it below for 1000 trials, and then for that output we look at what percentage of the time we see each of the numbers. So from this it looks as though we see our first duplicate most often on the 5th, 4th and 6th purchases.

saw_repeats = pd.Series(simulation1(n_trials=1000))

saw_repeats.value_counts(normalize=True)

5 0.196

4 0.183

6 0.169

7 0.124

3 0.107

8 0.081

2 0.068

9 0.045

10 0.013

11 0.011

12 0.002

13 0.001

dtype: float64

What if we ran more trials? Let’s try n=10000.

saw_repeats = pd.Series(simulation1(n_trials=10000))

saw_repeats.value_counts(normalize=True)

5 0.1803

6 0.1584

4 0.1570

3 0.1313

7 0.1203

8 0.0840

2 0.0705

9 0.0524

10 0.0260

11 0.0120

12 0.0052

13 0.0021

14 0.0005

dtype: float64

Now things are looking a bit different, but still we are most likely to see our first repeat on our fifth purchase. Let’s try to run even more simulations!

saw_repeats = pd.Series(simulation1(n_trials=100000))

saw_repeats.value_counts(normalize=True)

5 0.17462

4 0.16236

6 0.15536

3 0.12794

7 0.12298

8 0.08709

2 0.07019

9 0.05247

10 0.02806

11 0.01245

12 0.00474

13 0.00129

14 0.00037

15 0.00008

dtype: float64

We can plot the output:

So we see that (of course) you will never get a repeat on your first purchase. On your fifth purchase you have about a 17% chance of getting your first duplicate. For the higher numbers, notice the probabilities are very low. This is because you are very unlikely to get your first duplicate on your 10th purchase, because it is so unlikely for you to have made 9 other purchases without duplicates.

Even though my probability of getting my first duplicate is highest on the fifth purchase, that probability is still quite low at about 17%.

Now, we might want to start thinking about combining the probabilities.

The probability that I would get my first duplicate on my 2nd OR 3rd OR 4th or 5th purchase is:

saw_repeats.value_counts(normalize=True).sort_index().iloc[:4].sum()

0.53511

So, even though the probability of me getting my first duplicate on any of these purchases individually is quite low (less than 20% for each), cumulatively the chance I see my first duplicate (and my first disappointment) within my first 5 purchases is above 50%.

So if I start collecting these badges, the chance of me seeing a duplicate in my first 5 badges is above 50%. However that might not be so bad, because even if I get a duplicate at this stage, with so few badges in my collection it still feels as though for any individual purchase I am more likely to get a new badge than one I already have.

Say for example I have: [“Ollie”, “Teddy”, “Jimmy Pesto”, “Teddy”], then I still might want to keep collecting and making purchases, my gut feeling would be that there are still a lot of badges out there I don’t have (13 of them). This brings us nicely to the next question.

At what point am I more likely to get a duplicate than to get a new pin. When does the probability of a duplicate become greater than 50%?

Part 2: I can’t stop buying badges

So we will now try to investigate when should I expect that I am more likely to buy a duplicate than a new badge.

Answering these types of questions precisely can become complicated, especially if we take into account the precise badges that you have. For example if you have Bob Belcher, Louise Belcher, and Gene Belcher, each of those pins has a probability of 2/20, and so you are more likely to get a duplicate on your fourth badge if you have those three than if you had another set of 3 where their individual probabilities were 1/20.

What we will do is use a simulation to get an estimate. We will simulate buying say 100 badges (for example), one after the other. At each stage we mark whether or not this badge is a duplicate or is new. We then repeat this many times. Then for the nth purchases we can look at the number of times that nth purchase was a duplicate and the number of times it was a new badge.

def simulation2(n_purchases=100, n_trials=1000):

outcomes=[]

for i in range(n_trials):

collection=[]

new_card=[]

for j in range(n_purchases):

badge = np.random.choice(probs)

#Check whether or not we already have this badge

if badge in collection:

new_card.append(False)

else:

new_card.append(True)

collection.append(badge)#Add the badge to the collection

outcomes.append(new_card)

return np.array(outcomes)

We should think of the output of this simulation as a matrix with n_trials rows and n_purchases columns. The probability of getting a new card on your mth purchase is the percentage of ‘True’s in the mth column. We will do a small toy example first to show how it works.

mat = simulation2(n_purchases=5, n_trials=2)

mat

array([[ True, True, True, True, True],

[ True, True, True, True, False]])

We sum the columns (True = 1 and False = 0), and then divide by the total number of rows.

np.sum(mat,axis=0)/len(mat)

array([1. , 1. , 1. , 1. , 0.5])

In the very small example above (2 trials), we had a unique badge both times for the first purchase, and so the probability is 1. For the fifth purchase we got a unique purchase once and a duplicate once and so the probability there is 0.5 .

Of course this is a tiny example just to show how the code works.

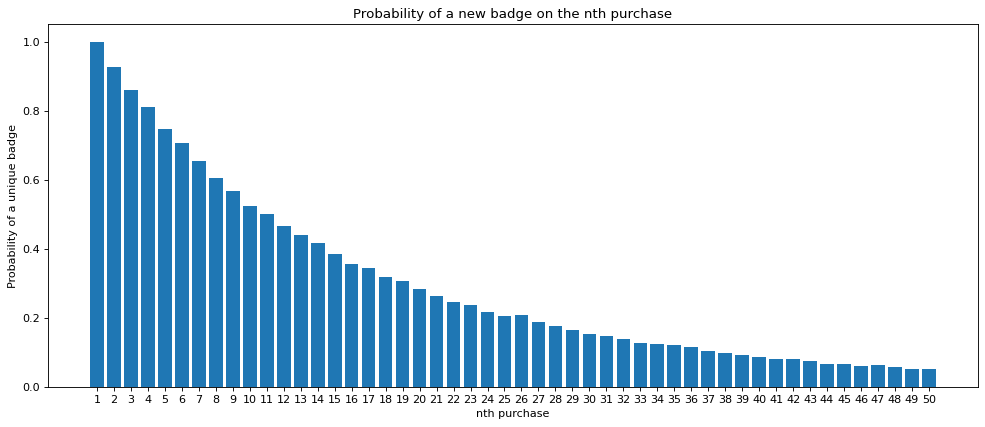

We will do 10000 simulations of 50 purchases.

mat = simulation2(n_purchases=50, n_trials=10000)

probability_of_unique = np.sum(mat, axis=0)/len(mat)

print("The probability of getting a unique card drops to below 0.5 for the first time on the {}th purchase. Your probability of getting a new card here is {}.".format(1+np.argmax(probability_of_unique<0.5),probability_of_unique[np.argmax(probability_of_unique<0.5)]))

#Note in 1+np.argmax(probability_of_unique<0.5), we are adding one because index starts at 0

The probability of getting a unique card drops to below 0.5 for the first time on the 12th purchase.

Your probability of getting a new card here is 0.4655.

Interesting!

We can see in the graph above the probabilities getting very close to zero for the higher numbers of purchases. This brings us nicely to our final question. How many purchases of blind boxes should I expect to make before I get the complete collection of 16 badges?

Part 3: Gotta catch them all

In this section we run a simulation to see how many blind boxes I would need to buy to get the complete collection of 16 badges.

def simulation3(n_trials=1000):

purchases_until_complete = []

for i in range(n_trials):

collection = []

while len(set(collection))<16:

badge = np.random.choice(probs)

collection.append(badge)

#We have the complete collection now

purchases_until_complete.append(len(collection))

return purchases_until_complete

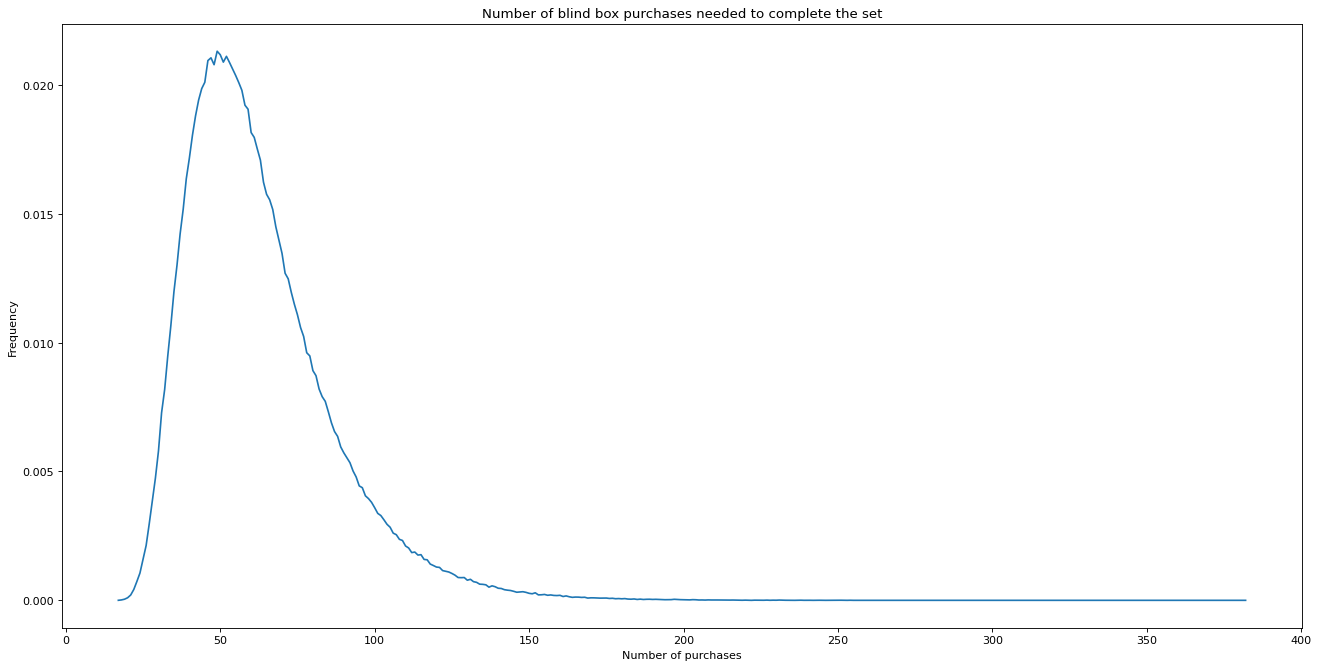

We run the simulation for 1000000 trials. In each trial we repeatedly simulate buying a blind box, and we record how many boxes we need to buy before we have the complete set of 16 badges.

results = pd.Series(simulation3(n_trials=1000000)).value_counts(normalize=True).sort_index()

The results are plotted below.

What is the most common (modal) value for the number of purchases to get the whole collection?

results.argmax()

32

results.max()

0.021307

But only 2% of people did it in this number, so incredibly small!!

What was the worst case we saw in our simulation?

results.index.max()

382

Wow that would really suck!

What was the best case we saw?

results.index.min()

17

Even in all the simulations we ran nobody got it in a perfect 16.

By how many purchases did 50% of people have the complete collection?

results[results.index <= 58].sum()

0.511562

results[results.index <= 57].sum()

0.492349

So c. 50% of people would have the complete collection by their 58th purchase.

results[results.index <= 100].sum()

0.9307109999999998

93% of people would have completed their collection by their 100th purchase.

Now, it looks as though on the website if I set the quantity to 20, I can buy the ‘full display box’. I am assuming this means I would get the full set (plus duplicates for each of the four badges with probability 2/20). This would work out at c. $140. On the other hand, my probability of having a complete collection by my 20th purchase of random blind boxes is a staggeringly small:

results[results.index <= 20].sum()

0.000162

So if I want the complete collection I am much better off buying the complete display than trying to obtain them by randomly buying the blind boxes.

Summary

In this article we have used Monte carlo methods (simulations) to explore probabilistic questions related to collectible badges based on the animated series ‘Bob’s Burgers’. Based on these simulations we found:

- The probability that I get a duplicate badge within my first 5 blind box purchases is above 50%.

- On average, by the 12th purchase you are more likely to get a duplicate than a new badge.

- Trying to complete the collection by buying blind boxes is hard - c. 50% of people would have the complete set of 16 badges by their 58th purchase. This means roughly half of people still would not have the complete collection by then. We see that about 7% of people still would not have the complete collection by their 100th purchase.